Community works

Surel's

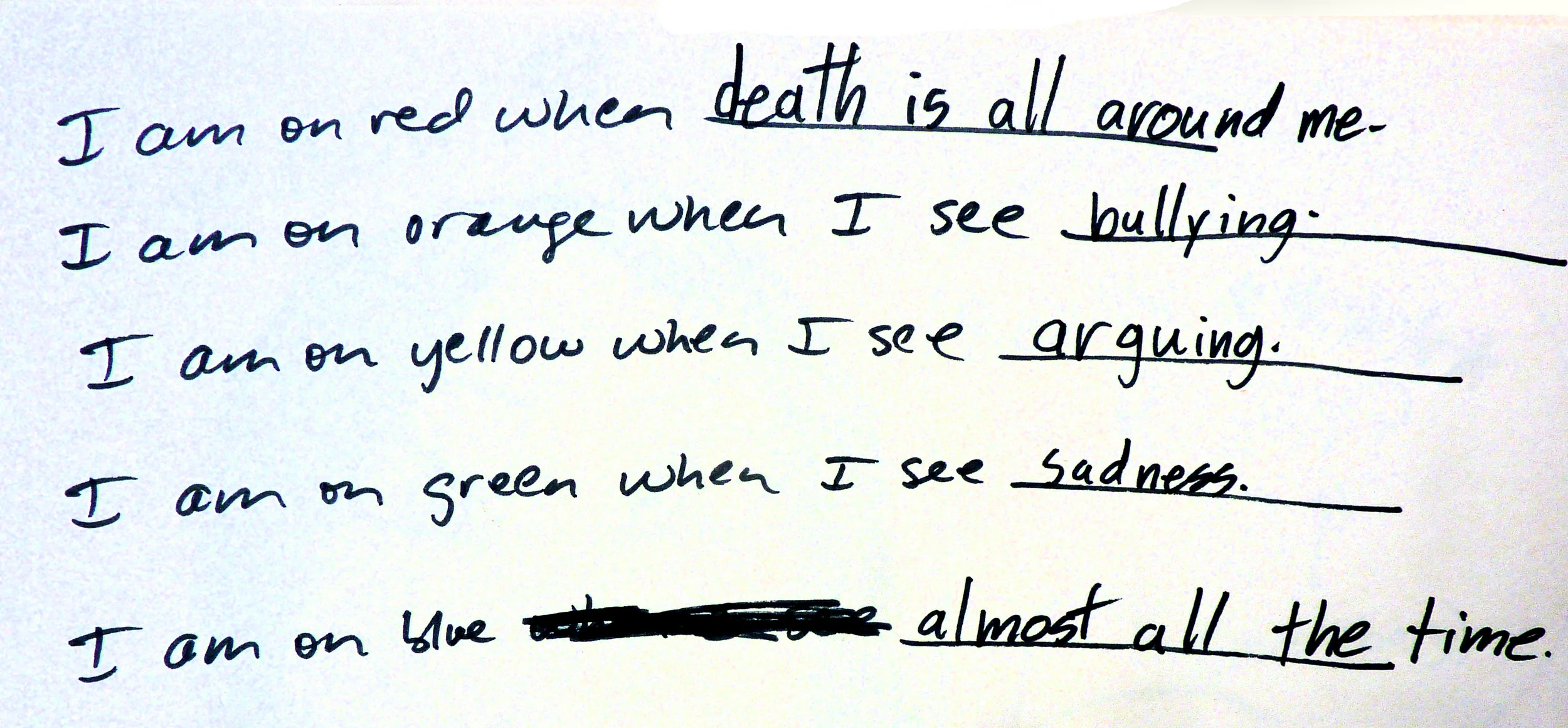

Color of Language and The Grump Meter at Surel’s Place, Boise Idaho

The Color of Language was a community art project to engage youth, families, and the broader Boise community in new conversation about art, feelings, and behavior in our personal and public lives. Janet Kaufman and Lynn Kaufman, co-authors of The Grump Meter: A Family Tool for Anger Control, envisioned the project and invited artist Hugh Merrill and Surel’s Place Arts Residency to partner with them. Working with the Grump Meter, a visual tool for anger management and self-regulation, the project reached over 800 participants, young people and families. Large banners were designed for the participating communities and now hang in community centers and school in Boise. The project is being continued in Kansas City in 2016 through Chameleon Arts with support from the ArtsKC Fund and the R.A. Long Foundation. We will be working with United Inner City Services and other communities through out the city

Art worker

ArtWorker Creativity and America Spiva Art Center 2013

In the wake of a disastrous tornado that destroyed a large portion of Joplin, Missouri on May 22, 2011, Artist Hugh Merrill, Chameleon Arts and Youth Development, Josie Mai, the Beehive Arts Collective, Jo Mueller and the Spiva Center for the Arts came together and formed a partnership to help the people of Southwest Missouri re-envision their city through the arts. The renewal of Joplin goes far beyond helping to rebuild the neighborhoods and families that were destroyed by the tornado. It was imperative to use this opportunity to provide the people of Joplin a means to express their fears, joys, beliefs, and concerns through contemporary relational aesthetic practice.

ArtWorker opened on May 18th 2013, coinciding directly with the second anniversary of an EF5 tornado strike on the city. The exhibition and arts events celebrated the rebirth of the community as well as commemorate their losses. The project sparked a new relationship between the Joplin community, contemporary art, and the Spiva Center for the Arts. This new creative process, historically based in Merrill’s previous explorations into interdisciplinary/community arts process facilitated a non-hierarchical arts events by merging the work of artists, poets, and playwrights with the voices of everyday folks living and working in the Joplin area. The exhibition and events were supported by a grant from the National Endowment to the Arts 2013.

In 2011, the same year that Hugh Merrill organized community arts action for the America: Now and Here exhibition in Kansas City, the artist was invited by Spiva Center for the Arts to exhibit Divergent Consistencies: Forty Years of Studio and Community Art. Merrill felt it would be more interesting to change the focus from a retrospective to an exhibition based on the goals, values and processes found in ANH.

"I hoped to encourage both residents and artists from Joplin to express their feelings and concerns about America through a series of thematic prompts. We were on the path to replicate, collaborate and evolve the ANH project for Joplin. The ANH vision was that the project would travel in converted semi-trucks to cities and small towns across America for a decade or more. As with many complex and ambitious creative projects, things did not go as planned. After a highly successful beginning in Kansas City the fortunes of ANH changed and what had started so successfully was forced to shut down."

Merrill partnered with Josie Mai, an artist, educator, and friend who was teaching at Missouri Southern State University in Joplin, and took the lead in reinventing the project for Spiva with the help of gallery coordinator Shaun Conroy and director Jo Mueller.

Acting as exhibiting artist, curator, and ringleader for the Joplin community arts actions, Merrill exhibited his own work in concert with pieces by Joplin area artists. Merrill's artwork provided the exhibition's themes: politics, iconic American monuments, the environment and ecology, diversity, and family. Visitors encountered America as envisioned by ArtWorkers from numerous disciplines: visual arts, music, dance and the literary arts. More than 500 people participated on opening night, and thousands more came to add their touches to the exhibit and events over the seven-week run of the event.

Download PDF version of exhibition book

Hard copies of the exhibition book can also be purchased for $15 a piece

through Chameleon Arts & Youth Development

or the Spiva Center for the Arts.

Pool's of belief

Interview on Pools of Belief installation conducted by Max Skorwider at the Impact Prinmaking Conference in Berlin, 2005

Max Skorwider is a graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts in Poznan, Poland. Max lives in Poznan and is a noted poster designer, artist, and contributor to the art magazine, Areton. He and Maja Wolna interview Hugh over a Piwo (beer) in The Proletarist Bar in Poznan, Poland, September 2005.

Max: Can you tell us about Pools of Belief?

Pools of Belief is a community art piece, performance, installation and exhibition. I created 4 graphic images of a children’s swimming pool filled with water. Each was about 4X4 feet in diameter. Floating in the pools are images of mousetraps shaped like boats. Trailing from the traps are narrow sheets of paper with the text “I believe in the New York Stock Exchange” and other such answers. The graphic pools are adhered to rubber mats that are easily moved from place to place. The pools were displayed in public places in Berlin and Poland where the people walking by are asked to participate by writing their own answer to the phrase “I believe in_________” on a narrow sheet of paper. They are then asked to place their “I believe in _________” paper strips in a mouse trap and place the trap on one of the graphic pools. All of their responses are kept for later exhibition.

I was able to work with a group of Polish art students who helped with the performances and installations. The Pools were taken out to locations in Berlin. In Poznan they were installed at the National Museum of Poland, and in front of the Zamek Cultural Center. The final installation/exhibition took place at the Academy of Fine Arts in Poznan.

Max: Are the pools a metaphor, and if they are what do they stand for? Or, why Pools? Why children’s pools?

We are a light society, a society of consumer goods, material desires, a society consumed by what is fun, goofy and playful. We are desire and we are life-style driven. Our time is much different than the old oppressed societies of Eastern Europe under Nazi occupation, then under communist occupation. If Poland is occupied now it is by Nike, Reebok and beer companies. So the first consideration was to create a visual metaphor for our consumer society and a shallow children’s pool seemed perfect. They are beautiful, clear, not only shallow but lacking in depth; they are made for fun and play; their borders are plastic and air. Old borders were steel and iron, barbed wire and guns; they called it the iron curtain. Now the western world lives in a continuous mall. The children’s pools act as a metaphor for national boundaries: children’s pools stand for realms of existence, countries, institutions and religions they stand for our light attitudes toward these institutions and concerns.

Max: What about the mousetraps? Where do they come in, and where does belief fit in?

A belief system is double edged; the values that keep a person a float in life are also a trap that blinds them from seeing the oppression they cause. A belief system centers us and provides moral and social guidance, political opinion and establishes our degree of tolerance. That same belief system is also the lens which prevents us from seeing others clearly. Belief is a trap that prevents us from seeing the harm and terror we do to others. So our belief system is both a trap and a boat and only when we see it as both can we step back and assess our actions. Absolute belief is like absolute power it is corrupting and always leads to some one getting killed. The metaphor is simple: belief is neither good nor bad. It has both positive and negative qualities. Belief both saves a person’s life, gives their life context and meaning and it traps a person makes them into oppressors.

Max: Have many people refused to put their beliefs in a trap?

No! Its amazing. Hundreds of people have stopped to participate in the action, and no one, no matter how sacred their belief is, no one has not completed the act of putting their belief in a trap and placing it on the graphic pools. I am not sure what that means, but it is interesting.

Max: You not only did public performances, but you did an installation of Pools of Belief in the rotunda at the Academia of Fine Arts in Poznan. How did the installation differ from the performance?

The installation of the pools at the Academia in Poznan is meant to have a deeper and darker weight than the public performance I described. The 4 pools and traps trailing people’s beliefs are placed on the floor of the gallery. On the walls are stenciled the words Belief Boat Float Saved Belief Trapped Confined Death Belief in English, Polish and German. There is a table in the gallery on which are pens and narrow sheets of paper and tape so people can add their thoughts and beliefs to the installation. The gallery setting provides the audience time, space and quiet to consider their beliefs in a more thoughtful and in a less entertaining and active space than the public performance. I watched people read the work, read others’ beliefs and contemplate the nature and meaning of the piece. They spent a good deal of time with the work.

Max: What will happen to the Pools of Belief will you continue the project into the future?

Yes, I envision the pools as a two-year project ending with an exhibition in Kansas City in March of 2007 at the Southern Graphics Council conference.

As the piece is performed/shown over 2 years, the weight and complexity of the piece increases with the documentation and records of beliefs accumulated. Where the pools are placed in the landscape determines or changes the reaction of the audience. Placing the pools in front of a historical site like the Jewish Cemetery in Berlin Germany is much different that placing the pools in a mall in Colorado Springs. The Final exhibit will document these changes.

Thanks to Max Skorwidcer, Miroslaw Pawlowski, Krztstof Molena, Beavais Lyons, and Maja Wolna.

Download a copy of this interview with photos (PDF, 311kb)

Download the Oceans of Desire brochure (PDF, 1.4mb)

Faces of the Homeless

Willa Gill Center, Kansas City, Kansas, June 2008

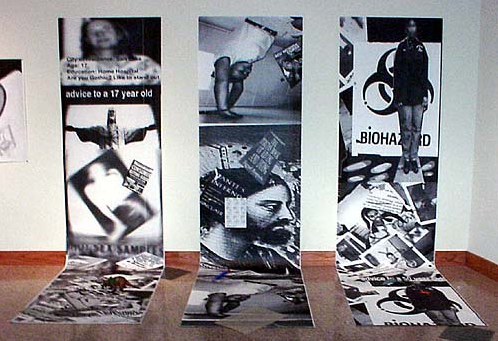

When we think of the homeless, we often envision a tattered older man holding a sign by the off ramp of a highway. The reality is far different. The average age of a homeless person in Kansas City, Kansas is 7 years old. In order to bring this story to a broader public audience, Hugh Merrill and Chameleon Arts and Youth Development began the community arts project, Faces of Homeless Youth. The goal of this project was to increase the self-worth and self-image of homeless teens in Kansas City, Kansas, while enhancing public understanding of the impact of homelessness on children and youth.

Working in collaboration, the Kansas City, Kansas Public Schools Homeless Liaison Staci Pratt and community artist and Kansas City Art Institute Professor Hugh Merrill guided a group of homeless teenagers living and going to school in Wyandotte County in creating journals, arts and performance projects over the past 9 months. This work then led to the production of a series of posters and large-scale graphic images of the youth scheduled for installation at the Willa Gill Resource Center in Kansas City, Kansas on June 20, 2008. The images are meant to help people connect with the reality of homelessness while providing the children with the skills to develop a coherent and insightful artistic voice, to support their academic ability, and to build self-esteem and community. The posters were also exhibited in Washington, DC in the fall of 2008, during the National Conference for the National Association of Educators for Homeless Children and Youth.

Mellennium voices

Millennium Voices

Dania Elementary School, Dania Breach, Florida, 1999-2000

Excerpt from Millennium Voices: Recreating a Community Through Listener-Centered Art

by Heather Lustfeldt

Heightening a sense of community through investigation of self-identity and collaboration define the project, Millennium Voices/Portrait of Self, in Dania Beach, Florida. This project involved the entire community of Dania Elementary School. Lasting nearly one year, from May 1999 to May 2000, Merrill made five trips to Dania to organize and facilitate this unique, creative interaction.

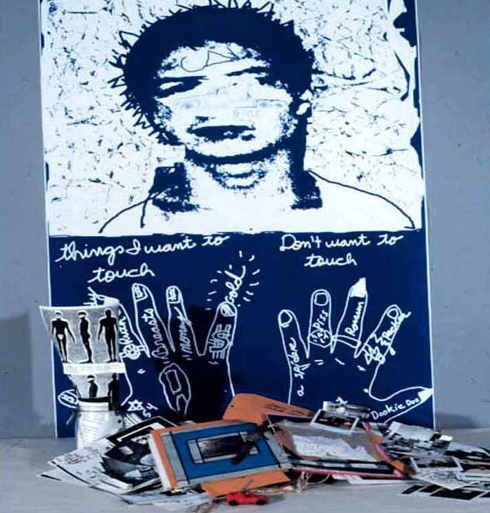

Three distinct components frame Millennium Voices/Portrait of Self. One aspect engaged the students in collecting personal archives, including copies of old family pictures, documents such as birth certificates, images of favorite objects and toys, personal notes, drawings, scraps of material, and the like.

Collected and compiled into notebooks over the course of several months, the process was an exercise in self-identity and memory resulting in what Merrill describes "as a lifetime living work of art having both function and a lifetime goal outside style and aesthetic content."

The creation of "a living communal archive" through collaboration between students teachers, parents and administrators, was then created inside the school. Collections of black and white photocopies included images of students' hands, toys and objects, family pictures, old class photos of teachers and candid photographs of students and teachers taken by Merrill. In a group effort, the students and teachers

installed these archival images in a layered collage covering the various walls of the school. Merrill explains the premise for Millennium Voices/Portrait of Self as follows:

"The issue is how we use art to change a community's relation to an institution–then change the way an institution sees itself so as to support the identity of the community—giving itself up to acknowledge your life and your heritage. Letting all of the kids put up photocopies of their family archives on the walls of the school is the creation of such a relationship. With the images up, the kids own the wall space; it's about them individually and about creating individual ownership of a public institution."

As a lasting component of the process, Merrill selected from the collage, creating a 150 foot graphic mural he describes as a "distillation" of the many images and experiences of the community interaction. The mural–a combination of painting, drawing, and traditional printmaking–is a digitally manipulated montage. Ultimately printed onto vinyl with special ink, the mural is a permanent installation spanning three buildings of the school and fastened directly to the concrete walls. It faces a busy highway (Dixie Highway) dividing the school from a failed vacant strip-mall. Abundant billboard advertising along the highway reinforces the commercial environs of the school and surrounding neighborhoods. Merrill references these factors in the mural augmented by a temporary installation of complementary graphic adhered to the school's surrounding sidewalks, a spontaneous encounter and visual cue for pedestrians to contemplate the nearby mural.

Looming eyes of children stare out from the mural, interspersed with fragmented portraits and vernacular images articulating a sense of history and place. Colorful strands of Seminole Indians, indigenous to the area but displaced in the event of colonization, also appear. Slices of red tomato reference Dania as a farming community that once produced huge crops of tomatoes eventually supplanted by housing and development. Collages of individual teachers past and present, group school pictures, images of children's palms, and the dangerous highway commingle. Bright yellow and blue skids transverse across and amidst the images, suggestive of speed and direction. Through this visual mélange, Merrill creates a subtle subversion–a critique of commercialism, mass media influences, and the commodification of children--by creating an artwork that duplicates a commercial construct, but defies commercial aims. The piece is a hybrid of vernacular murals and billboard advertising. The eyes of the children–unblinking, questioning, and disquieting--are not trying to sell a product, although the nature of the work begs this question, provoking a complex array of interpretations.

The full essay appears in Divergent Consistencies. More info on Publications page.

Art of Memory

Sanford-Kimpton Health Department Building, Columbia, Missouri, 2004

Interview between Hugh Merrill and artist and educator Eleanor Erskine Professor Portland State University, Portland, Oregon

Hugh, what was your approach to the Health Department project for Columbia and how was it different form other public art projects you have created?

My approach to public and community work is consistent in process and varied in outcome. I start with getting to know the individuals in the community. I do that through an archiving process called Portrait of Self. It is a process in which I interview and get people to provide me with their life stories, provide me with their family documentation and photos. The archive becomes the resource for the images to be created.

How did you apply that process to the Health Department in Columbia/Boone County?

First I had to understand what a health department does--who it touches. The Health Department and Family Health Clinic are comprised of a series of scientific and medical services. These include animal control, public health, a family clinic, and environmental science among many others. The clinic servesa broad and diverse community and is staffed by a committed group of professionals. I felt that the artwork for the building should respond to the function of the department, essentially reflecting the lives of the clinic's clientele. I wanted to create a visual environment that flowed through the architecture, unifying the various services and public spaces.

So part of your investigation is focused on the community, getting photos from people, hearing their stories and part is a formal response to the architecture. Is that right?

Yes, absolutely. It's partly a collection of imagery and stories from the community and partly a search for what will best function as an interactive part of the overall architectural design. Having seen the wonderful architectural plans of Kaylyn Monroe, I wanted to make artworks that would take advantage of the openness of the space and the beautiful natural light she designed into the building. I wanted the artwork to resonate with the richness and variety of construction materials used in the building: wood, concrete panels, translucent plastic, sheet metal and stained concrete.

What made you place the work in the building at tilted angles and at unexpected viewing levels?

The oval shapes and the decision to install the works throughout the building at raking angles and in unexpected wall positions reflected a counterpoint and complement to the beauty of the architectural grid. The building is a complex layer of grids, of visual starts and stops, of changing speeds and sounds. I wanted to create organic forms that fall at obtuse angles across and in opposition to the grids.

How did you begin, what was the first thing you do when you start on a public or percent for the arts project?

Rather than coming to the project with a preconceived idea of what the final work should look like, I employed the Portrait of Self community archiving process. I have used this process for nine years to collect content and visual information from communities internationally. Then, I use the collected information to make images concerning the community. Each project is different with differing environmental and architectural spaces. The outcome is designed to best suit the specifics of each community and institution.

Can you take me through the process?

Let me start with a short history. In 1996 I was invited to produce a collaborative installation with artist Christian Boltanski for the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art in Kansas City. Boltanski and I came up with a citywide installation project titled Our City Ourselves, which invited the residents of the Kansas City metropolitan area to bring their family photographs to the museum, copy; then install them on the walls. Several thousand people brought their family photographs to the museum, copied them and pinned their photographs to the walls. Soon the gallery was covered with Xerox prints from floor to ceiling.

Building on Our City Ourselves I devised a workbook/process, Portrait of Self, to assist in the recall of lost memory and to help a community document its daily life. I used the process to work with inner city high school students. The archives the students created were exhibited at the Kemper Museum in conjunction with the Boltanski exhibition.

Since then, I have used the Portrait of Self process for collecting content to produce public and percent-for-the-arts commissions and installations. Portrait of Self has been used to produce large graphic murals in Hollywood/Dania Beach, Florida. It also acted as the source of the installation for the Daum Museum Goddard Gallery in Sedalia Missouri, an installation at the Manchester Craftsman’s Guild in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and with FutureSelf in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

How did you begin to collect community information and stories in Columbia?

I began the process with an artist in residency through a grant by the City of Columbia Office of Cultural Affairs with the Missouri Arts Council to work with high school students at Hickman High School, Columbia. We created large digital collages from the items the students carried in their pockets and bags. These collages became the first layer of content for the images to be created for the health department. The archiving process was then shifted to the staff of the health department. They provided family photographs. Other images were taken from health department publications of the 1940’s and 50’s. Then I was invited to go to the Boone County Historical Society to look at their collection of glass plate photographs from the 1890’s. From that I selected a number of images that became the base layer of the digital prints.

What was the final outcome for the project?

I designed six series of prints for the building: the large oval digital prints mentioned before, four polysilk banners, 27 silkscreened text plaques of quotes given by the health staff, vinyl decals based on DNA structures, and digitally printed canvases. The works are non-stylistic, yet I attempted achieve a thematic

and formal continuity. All the various works were then installed in the building.

You said it was important for the works to flow through the building. Did the installation achieve what you expected?

Yes, I was very pleased with the outcome of the installation the work flows well from room to room I used the small brightly colored text plaques to activate large empty wall spaces. By placing the plaques at odd and out-of-the-way viewing positions the space loses its lingering institutional quality. The plaques and other works make for a much more playful and activated environment.

If you had to find one factor or quality that was at the heart to the project what would that be?

At the heart of the project are people, the people who were willing to share their lives and family documentation with me. Other people at the heart of the project were the wonderful staff at the health facility and the students at the high school; the architects, the individuals involved in the political work of the city and the county, Marie Hunter whose gifted work brought the project to fruition, and lastly the artists who assisted on the project. These included: Adelia Ganson, Caleb Hauck, Patrick Moonasar, and Miranda Young. Sharon Hartbauer and Greg Thompson.

Roeland Park Skate Park Sculpture Installation

Roeland Park, Kansas, 2004

Hugh Merrill was commissioned to produce sculptures for the new skate park in Roeland Park, Kansas. The park opened and the sculptures were unveiled October 10, 2004. Merrill produced three bronze sculptures from castings of skateboards and computer keyboards.

Merrill said:

“In designing the bronzes I was trying to speak about creativity as a force in the lives of contemporary young people. I wanted to unite the physical and cerebral elements of creativity into a single work. The skateboards symbolize physical creativity and the keyboards the cerebral element. Together they unite the mind-body duality.

"They reference two processes of surfing and I wanted them to be fun, something the young people who use the park could relate to as art.

"Bronze was important because it is a public and traditional art material. Bronze is the metal of memorials and statues of famous and forgotten guys. I wanted the notion of skateboarding and web surfacing to be “memorialized” as bronze sculptures."

Merrill also produced 10 brass text plaques using literary quotes and poetry forms that will be installed in the park at a later date. Merrill described the plaques as a metaphysical element to facilitate conversations, and discussion by the people who use the park.

Goddard Gallery

Daum Museum of Contemporary Art, Sedalia, Missouri, 2000

Artist Statement

Humans were once defined as tool users, until it became apparent that even insects use tools. It is not solely our rationality that defines our uniqueness but also our irrational imagination. It is our ability to use all that is around us, the objects, the air, language and memory as poetic possibility. Everything we see, touch, do and remember is a poetic tool. For instance, when my 5 year old son takes the corkscrew off the table and it becomes a robot, a plane, or a universe, he is defining humanity though the infinite possibility of our poetic imagination. An imagination that is all to often schooled out of us.

Much of my studio work is an attempt to combine real first person experience and unrestricted poetic imagination. Over the past decade I have worked with incarcerated youths and inner city communities to guide these communities in producing personal archives which are exhibited in museums and community spaces as contemporary art works. In my prints, paintings and installations, in my private studio exploration I use my memory, experience and the collected visual resources of these first person interactions to guide, shade direct and inform the discover of surface and image in my studio work.

What is the outcome? What do I hope for? is beauty, deep sadness and hope.

portrait of self

Introduction from Portrait of Self workbook

by Adelia Ganson

Everyone is an artist. All people have the ability to make meaningful, insightful, and healing work.

Hugh Merrill says:

"Community art is a process that nurtures awareness and celebrations of others' aliveness . . . a process to move the community from the habit of consuming and watching culture to the ritual of producing and articulating culture."

Portrait of Self (POS) is Merrill's proprietary method of archiving information for use in collaborative community and public arts projects. Each student or participant is invited to bring with them chosen effects, photographs or other items they feel are representative of them.

A process designed to help participants express the many factors that make up who they are, one of the most effective aspects of POS is that it creates a learning situation where anyone can produce original, creative work. Simplicity is key as the work is inspired from nothing more than personal observations made in the course of everyday life.

Xerography, photography, drawing, and collage are all explored to create a library of images for potential use in creative projects and exhibitions. These items are collated, sorted, and re-contextualized by artist/facilitators, the participating community, and students who re-examine the raw data and turn it into visual communication and personal expression. The archives of information created by varying communities have been turned into large graphic murals, art books, installations, performance, poetry, and digital projects.

A collaborative project at the Kemper Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri in 1998 evolved into the POScurriculum. Merrill's collaboration with French conceptual artist Christian Boltanski resulted in the citywide community arts project Our City: Ourselves exhibited alongside Boltanski's Who We Are: Portrait of a Community event. An advertising circular in the Kansas City Star newspaper invited local residents to bring personal items and photographs to the museum for direct participation in the gallery show. These items were Xeroxed, and a large-scale collage was created that instantly reflected the audience and, by extension, the greater community.

At that time, Merrill's primary interest was in people who were marginalized by society and how they disappeared into political rhetoric or simply fell through the cracks in the social safety net. Boltanski's interests were fundamentally different, yet similar. He was interested in people who had physically disappeared, leaving behind photos and keepsakes, as well as personal possessions. These items function as ghostlike ephemera with no place to go, belonging to no one. Through this contrast, the project became the impetus for much of Merrill's community artwork from 1998 to the present.

Download a free PDF ebook of the Portrait of Self workbook

Hard copies also available for $16 (+ shipping/handling) at Lulu

Manchester Craftsmen's Guild

Hugh Merrill was invited by Mr. Jan Raihle Director and Anne Seppanen Curator of the Darlarnas Museum in Falun Sweden to create the installation Wish-Flush: Antithesis of Choices and Desires for the Falun Print Triennial August to November 2007 in Falun Sweden. The Darlarnas curators had seen Pool of Belief, an arts action and installation Merrill exhibited at the Polish National Art Museum in Poznan Poland in 2005, and were interested in having Merrill create a new work based on “Pools” for the Darlarnas Museum/Falun Print Triennial 2007. Merrill, working in collaboration with artist and close friend Patrick Moonasar, devised an interactive installation of graphic digitally printed images of children’s swimming pools filled with consumer goods printed as rubber floor mats. Merrill lectured on the project at the Darlarnas Museum in October 2007 as part of the Triennial.

Wish-Flush was also performed at the Kansas City, Kansas YWCA with StoneLion Puppet Theatre on Earth Day 2008.

Download the Oceans of Desire brochure (PDF, 1.4mb)

Cuba

In 2004, Hugh Merrill had the opportunity to go to Havana, Cuba and Antigua, Guatemala with the Medical Missions Foundations of Kansas City. The foundation is committed to taking artists on their medical trips to work with children and to make cultural connections with artists in the counties the mission is working with.

Kenya

The trip was organized by Kansas City artist and educator Josie Mai and Transformational Journeys Inc. to work with the Sisters of Charity Mission in the Huruma district of Nairobi. Transformational Journeys is a not-for-profit travel organization that organizes group trips dedicated to positive social agenda and mutual service.

Josie Mai had previously worked with Mother Theresa's Missions of Charity in Nairobi. She envisioned and organized the trip to work at the mission, which combined artists and allied health professionals and students from the University of Kansas Medical Center.

For most people it is easy to see how special educators can use their training and skills to help orphaned and "crippled" children (crippled is the term used in Kenya). How artists can apply their skills is generally less obvious. Josie, however, understood the importance of combining medical and artistic interactions for the children of Huruma.

Working with four artists from the Kuona Trust Museum Art Studio in Nairobi the team built a playground/sculpture park on the grounds of the Charity Mission.

Reconcile

Please feel free to print out multiples of this poster and use them as part of your own community art project. Take them to schools and community centres and have that community sign and write on them. Have them make their own reconciliation works.